Distinguishing between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s Disease hasn’t always been easy for the medical community. The lines between the two conditions are blurry to say the least as researchers dig into ways to keep MCI from progressing to other forms of dementia such as Alzheimer’s.

It’s important to note that not all patients diagnosed with MCI go on to suffer from Alzheimer’s, but nearly all cases of Alzheimer’s begin with MCI. The danger of not monitoring it closely or having a well-defined understanding of each is that older adults suffering from Alzheimer’s viewed as MCI may not receive the care they require.

Mild Cognitive Impairment Defined

How MCI is defined has evolved over the years. It’s commonly thought of as the period between healthy cognitive function and the onset of Alzheimer’s.

Initially, guidelines for MCI diagnosis only allowed for someone to show impairment in terms of memory. Other cognitive functions had to continue as normal. That definition was altered to allow for problems in reasoning and judgment, but a person had to continue functioning as they normally would in their daily life. If their activities of daily living changed radically, the diagnosis was typically dementia or the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Research teams from the Alzheimer’s Association and National Institutes of Aging then supported a revised definition of MCI which allowed for mild impairment in activities of daily living as well as some of the cognitive challenges outlined above. As a result, drawing a clear line between Alzheimer’s and MCI continued to prove difficult.

Where is the Line?

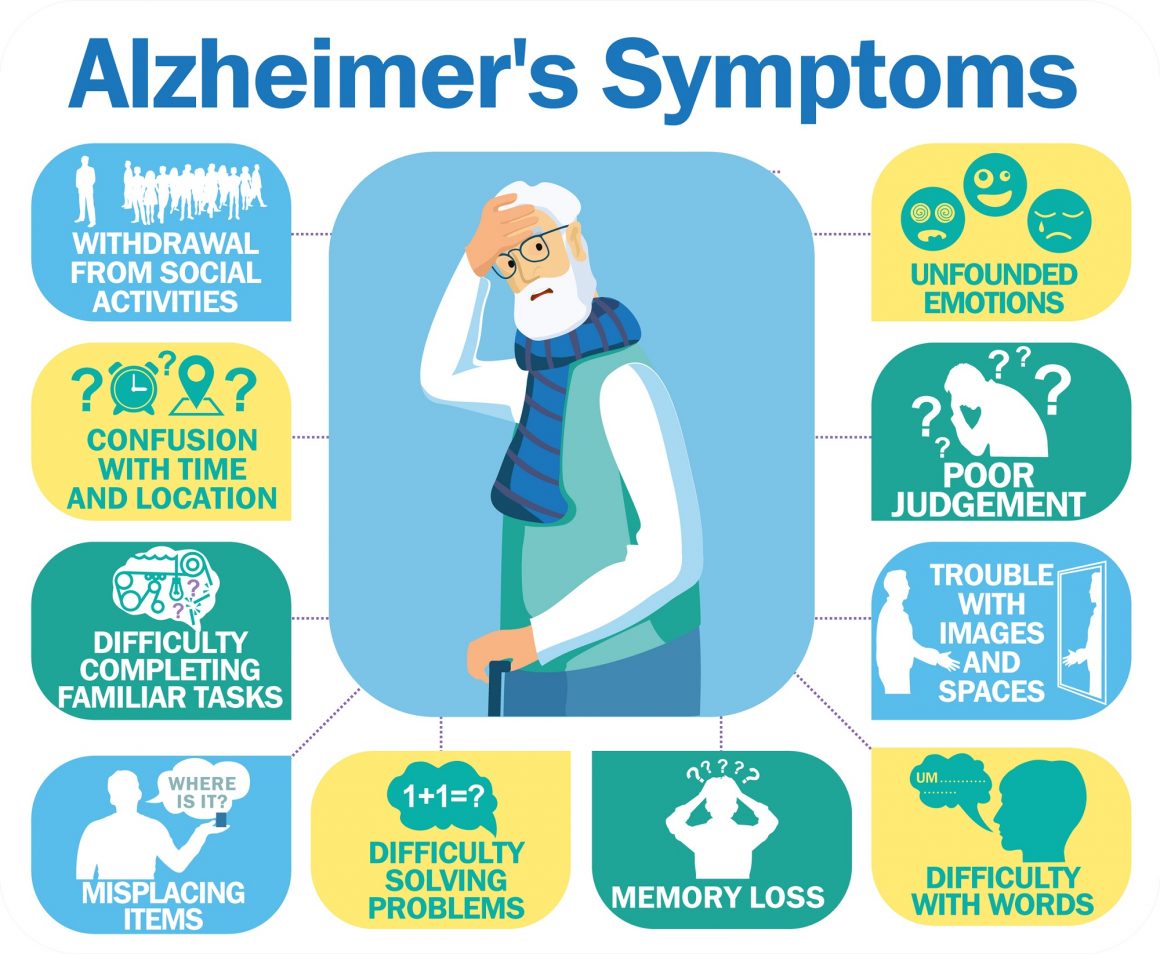

According to the National Institutes on Aging, MCI patients exhibit more severe problems associated with memory than the average person their age, but they don’t display personality changes or difficulties they classify as moderate symptoms of Alzheimer’s such as:

- Hallucinations and paranoia

- Angry outbursts, restlessness and agitation

- Trouble with reading, writing and math

- Short attention span

- Inability to think logically

- Failure to perform multi-step tasks

- Impulsiveness

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, MCI primarily affects specific functions within the brain. For example, a deterioration of memory function is labelled “amnestic MCI.” Signs of this include a person forgetting things they would have easily recalled in the past, or routine things like appointments or conversations they had recently.

If the condition affects skills not associated with memory, it’s known as “nonamnestic MCI.” This can include inhibited decision making, visual perception, loss of timing senses or the inability to execute the sequence of steps needed to complete a complex task.

These distinctions are important as they help medical professionals and researchers create a clearer picture of where cognitive decline is at the present time and what its progression looks like. Older adults who don’t show signs of the condition progressing toward Alzheimer’s or dementia can continue to live independently and function more normally later into life.

For those whose condition does progress however, it’s important that interventions and care be delivered at the right time. During a period of extensive research, innovative ideas for new treatments are surfacing. But as we wait for a day when personalized treatments can preserve or repair cognitive function, one the most important things older adults and those who care for them can do is monitor MCI after diagnosis and understand the difference between it and Alzheimer’s Disease.