As years of medical research yields unlimited promise for treatment of a wide range of conditions, pharmaceuticals are stepping into the spotlight to offer treatment options for conditions once considered uncurable.

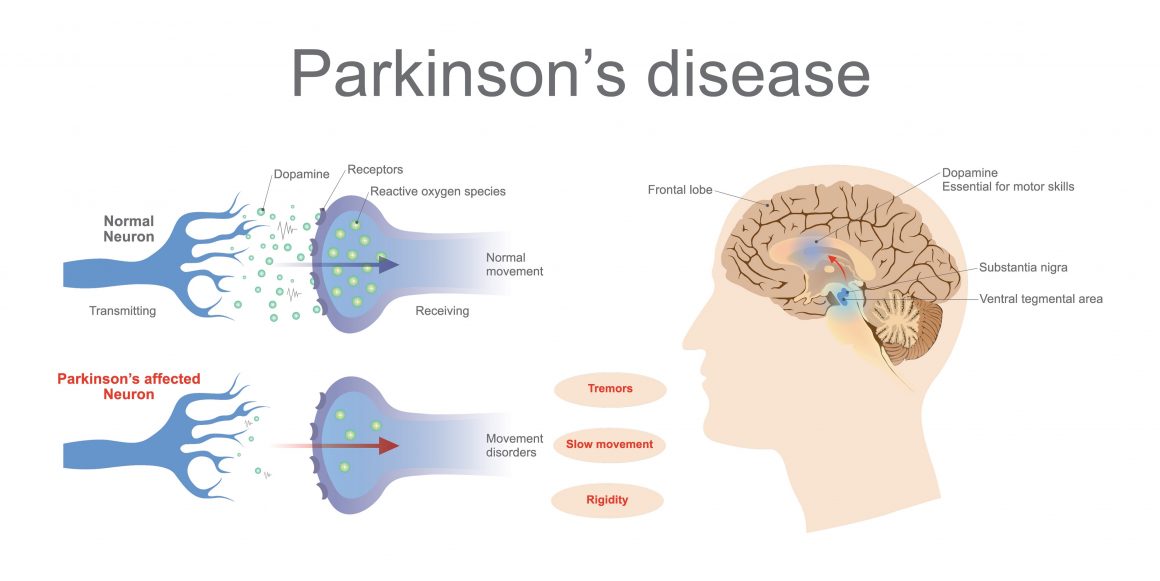

Parkinson’s disease is one of those conditions that has no cure, but recent research suggests that answers already exist and has shown that symptoms of the disease can be kept at bay.

Around 60,000 Americans are diagnosed with this neurodegenerative condition each year, with the vast majority of new cases diagnosed after the age of 50. Stopping the disease from progressing can make a big difference in the quality of life someone leads in their later years, which is why a recent development around the blood pressure medication felodipine could prove to be of importance for those suffering from the disease.

What is Felodipine?

Used to treat hypertension (high blood pressure), felodipine acts as a calcium channel blocker which relaxes blood vessels so that they widen and increase blood flow as a result.

The drug helps prevent strokes, heart attack and renal failure. It is taken once per day orally, typically on an empty stomach.

Felodipine and Parkinson’s

A paper published in the journal Nature Communications outlines how felodipine has shown promise in animal studies in addressing the accumulation of toxic proteins common in the development of neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease.

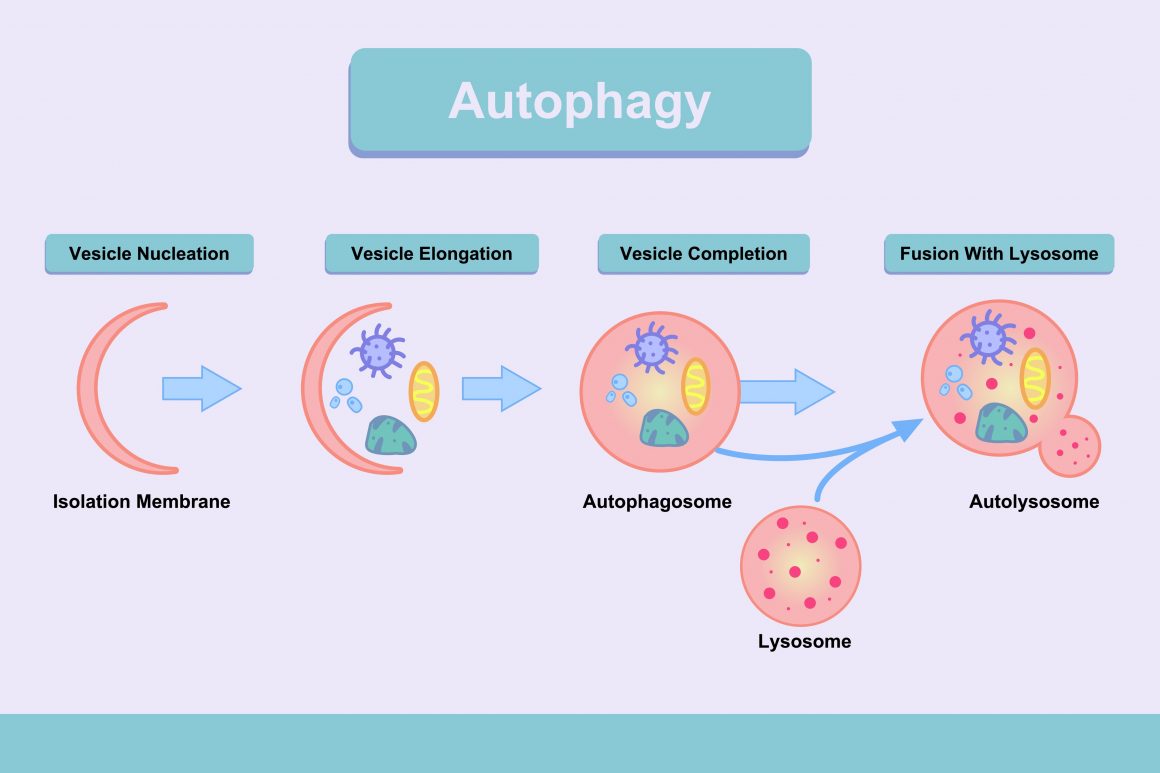

According to the study, “felodipine induces autophagy” in neurons and enhances removal of a range of disease-causing proteins.” Autophagy aides in the clearance of these proteins and diminishes their toxicity in animal models, leading researchers to re-position/re-profile existing compounds used in humans to identify which ones could induce autophagy in the brain.

Autophagy is typically inhibited by neurodegenerative conditions, so any process that boosts autophagy is of interest to researchers looking for potential treatments to these conditions. However, a key factor in the success of felodipine is its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. Scientists have tested a number of drugs through the years, but few have crossed the barrier and proven useful.

This adds evidence to a 2008 study from the American Academy of Neurology that involved 7,374 people over age 40. Half of them had Parkinson’s disease while the other half did not. Among both groups, nearly half used high blood pressure medications, such as calcium channel blockers.

The study concluded that long-term users of calcium channel blockers to treat high blood pressure lowered their risk of Parkinson’s disease by 23% compared to people who didn’t take the drugs.

The repositioning of an already existing drug is attractive in the eye of researchers due to the ability to transition from pre-clinical models to using the drug in treating Parkinson’s patients. The fact that tolerability and toxicity have already been established for the drug means that approval for use with humans could be quicker, however, there is a catch.

Dosages administered to mice, for example, included concentrations that are more than two times the amount typically given to patients for hypertension. The study concluded that “this situation could result in effects of the drug in mice that would not be seen in humans taking conventional doses.” If the treatment of humans required much higher concentrations of the drug, that would likely be associated with an increased risk of side effects.