Cognitive decline may seem like an unavoidable part of the aging process, but researchers have been examining if attempting to train the brain could help delay or even prevent the signs and symptoms of cognitive decline.

This cognitive training takes shape in two forms typically. One is compensatory, or training the brain to achieve new tasks by compensating cognitive issues. This might be done by using external reminders such as notes, environmental cues or calendars. Internally, the person may learn to categorize things more effectively or visualize the information they need to recall.

The other method is restorative, or in other words, an attempt to improve cognitive function through exercising certain cognitive domains to work better in a more general sense. Memory and attention games are just a couple methods of doing this. This generalized training is meant to enhance the brain’s ability to perform both similar types of tasks as well as tasks related to activities of daily living.

Currently there are studies being conducted using computerized cognitive training for older adults, with some researchers hypothesizing that if the treatment is proven effective, it could alter the cognitive aging path for adults age 65-85.

How Can Older Adults Improve Their Cognitive Skills?

Cognitive function can be improved by a number of factors including physical activity, social stimulation and cognitive training. There are multiple clinical trials looking at cognitive training which include comparing it against a group whose treatment is physical activity. In the end, both boost enhanced function, but in different parts of the brain.

Cognitive training aside, regular physical activity is a good idea as it has significant benefits for both body and mind. As for the cognitive training aspect, one study from the University of Texas used a method they developed in-house at the university’s Center for Brain Health called Strategic Memory Advanced Reasoning Training (SMART).

Over the course of 12 weeks, cognitive training tasks designed to help seniors focus on the most relevant information in a story through strategic attention exercises, streamline how they synthesize information they come across in daily life through integrated reasoning methods and spark innovative thinking by improving their ability to identify problems and update their ideas and perspectives.

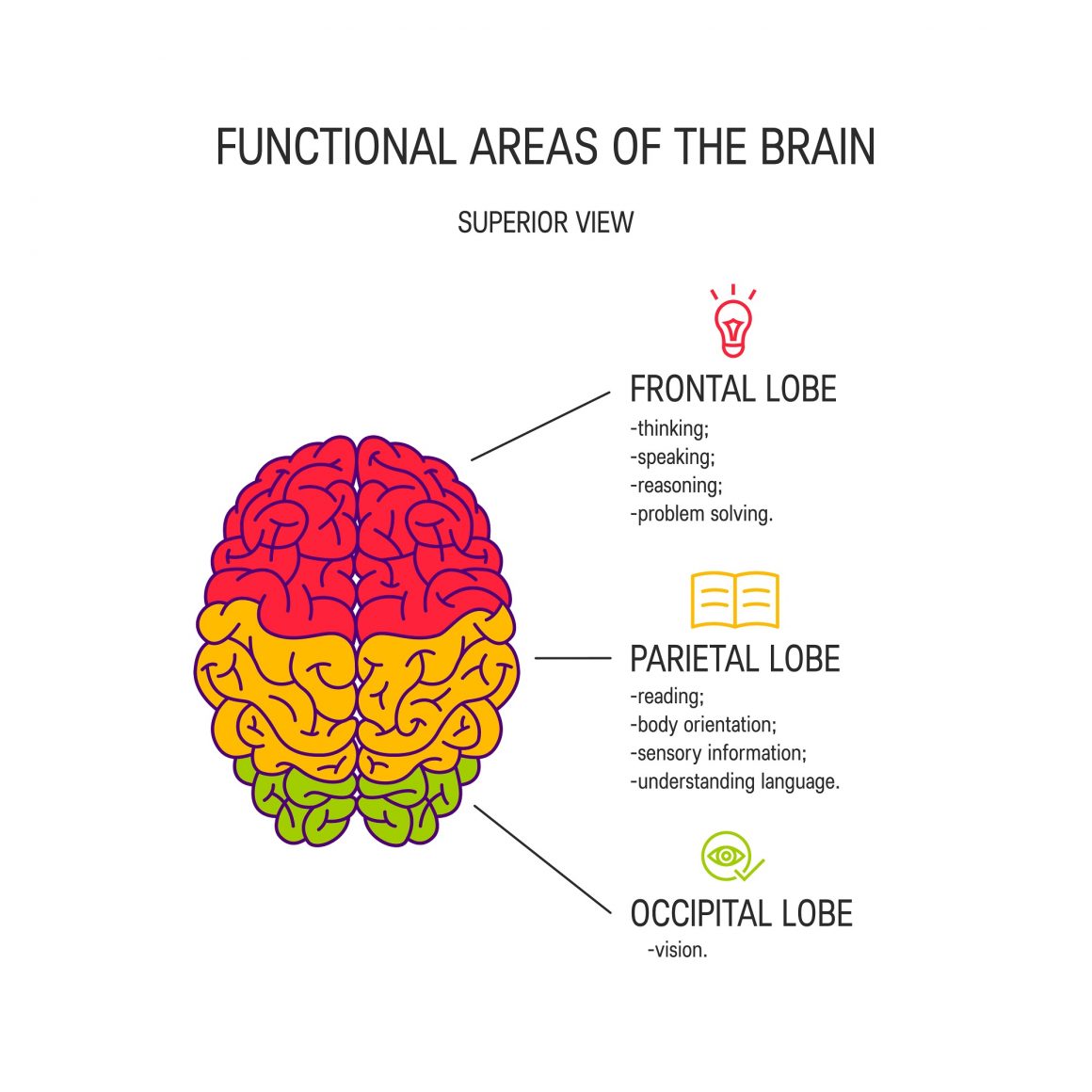

The cognitive training group showed a significant increase in the association between reaction time and frontal lobe activity. Faster reaction times were associated with lower frontal lobe activity, which more closely resembles the efficiency of neural activity found in younger adults.

Does Your Ability to Learn Decrease with Age?

A study published in the journal Psychology Science looked at the effect of two activities that could easily be achieved by healthy seniors, both separately and in concert with each other. The tasks were quilting and photography. The goal was to assess the impact of sustained engagement in an activity, or roughly about 15 hours per week working on something.

The photography tasks also included the use of the popular photo editing software, Photoshop. Seniors were given instructions on how to use it, which was “particularly demanding of episodic memory and reasoning, given that participants had to remember many complex verbal instructions to use both the software and camera,” the study reported.

The quilting group learned basic skills and eventually progressed to complete more complex, individual projects using computer-driven sewing machines by the end of the 12 weeks. A third group did both activities, meaning all three were active in what is called “productive engagement,” or the act of learning a demanding new skill.

This is in direct contrast to a control group, which experienced receptive-engagement. Participants engaged in novel activities and socialized for 15 hours a week, but did not actively acquire new skills.

In the end, researchers reported the most significant improvements came in the photo group. While episodic memory improved across the three productive engagement groups far more than the receptive group, the three productive groups were not equal. The complexity of the photo group’s task created more benefit for the older adult than the quilting group.

“We found evidence that sustained effort to acquire a demanding new skill improved episodic memory and no evidence suggesting that socializing, information exchange, and novelty alone facilitated cognitive function,” the researchers concluded.